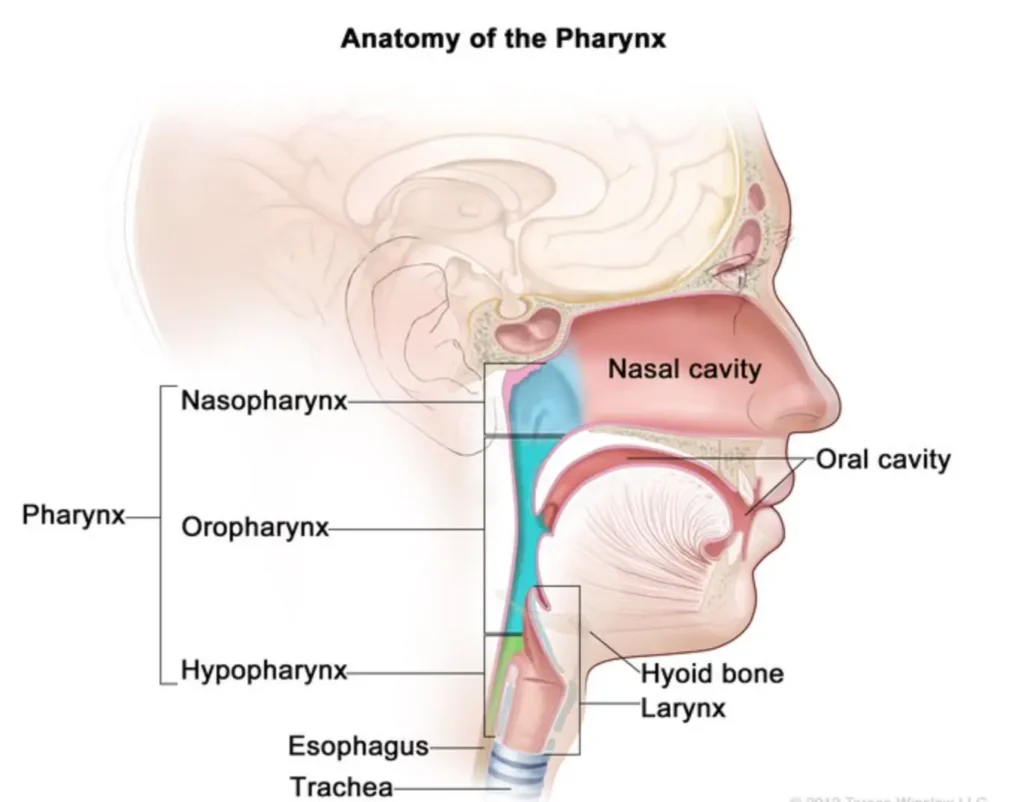

“In our book, Your Designed Body [Howard Glicksman and Steve Laufmann], we apply a five-part test for evaluating ostensible instances of bad design. This test can help determine whether we’re looking at a bad design, or simply a bad argument. Let’s consider the example of the human pharynx. Is it poorly engineered? The figure above shows that the pharynx is the common entry for both the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts. Whatever is ingested can potentially go down the airway and cause obstruction, which can result in death by choking. Some insist that the pharynx is therefore miserably designed, something no wise designer would engineer, but that evolution, with its trial-and-error messiness, very well might [e.g., Nathan Kentws and Abby Hafer]. These arguments are riddled with problems. To see why, we need to take a closer look at the human pharynx. In addition to the structures identified in the figure above, fifty different pairs of muscles, connected by six different nerves, are needed to swallow. After food in the mouth has been formed into a small ball (bolus), the tongue voluntarily moves it to the pharynx, which automatically triggers the involuntary swallow reflex. As the bolus enters, the pharynx sends sensory information to the swallow center in the brainstem, which immediately turns off respiration so that air is not breathed in during swallowing. This prevents the lungs from drawing food into the airway. The brainstem also sends precisely ordered signals telling the various muscles to contract and move the bolus downward into the esophagus, bypassing the airway. This takes about a second. As swallowing begins, several muscles contract to move the bolus into the pharynx, while moving the back of the palate and the upper pharynx close together to close off the path to the nose. Next comes the tricky part. The bolus has been blocked from going up into the nose, and muscular contraction is hurtling it down towards the airway and the esophagus. Three separate actions take place to protect the airway. First, muscles contract to close the larynx, which is the gateway to the lungs. Second, other muscles move the larynx up and forward (which you can feel in the front of your neck while swallowing) to hide it under the floor of the mouth and the base of the tongue while being protected by the epiglottis. Third, this action, combined with other muscular activity, opens the upper esophagus to allow the bolus to enter. The timing and coordination are remarkable. While critics seem to miss the amazing design of this system, it should give the reader pause. Somehow, swallowing happens, usually without incident, a thousand times a day. Where did the information come from that specifies the size, shape, position, and range of movement of the pharynx, each of its nearby structures, and the fifty pairs of muscles involved in swallowing? How could such a system come about gradually, by accident?”

Evolution News & Science Today, Dec. 14, 2022